What if grades didn’t exist?

I lived like a goddess for the first 6 years of my K-12 education. This was because I did not attend traditional elementary school: I was homeschooled and my parents did not grade me. When I started going to public school in 7th grade (you can imagine the chaos), I was surprised to find myself one of the top of my class. I came to public school with an entrenched love of learning that research and professionals in conversations around me are saying comes from a deeply instilled intrinsic motivation, not an extrinsic one. Good grades, while nice to get, were not and have never been my main motivation. This is because I learned in the best way: in conversation with a supportive community.

Now, in one of my jobs, I tutor high schoolers. They say they want to get good grades, but that motivation alone does not change their behaviors. What changes their behaviors is the enjoyableness of learning in dialogue with me, other teachers and adjacent supporters of their education; they do their best learning in conversation. Learning Difference experts and other professionals say this is the best way to learn because it makes learning fulfilling and even fun to explore in community: it builds that intrinsic motivation.

Motivation in general is a tricky word. It’s the pink dragon that we educators are always trying to rustle out of the bushes of our students’ intellects.

I think the best definition of motivation comes from the Drs. Dean and Ayesha Sherzai’s book, The 30 Day Alzheimer’s Solution. In seeking to help people engage with their 30-day brain-boosting diet, they describe motivation as more like an action than a thing we have. They go so far as to relate it to love: you have to work at it and build it, much as you would in a relationship. I had not heard this before, but it’s quickly re-writing pathways in my own brain.

So, what does this have to do with taking grades out of school? I think many of us have felt that grades provide some motivation for students who may lack an intrinsic love of learning; they learn just enough to help them pass their classes and get them through college. But the problem therein is that grades promote the anxiety and superficial motivation which make learning unenjoyable or do not promote life-long learning. This notion of life-long learning is becoming a key outcome in community colleges in my area where I am a faculty member.

We’ve thought of grades as a way to show students how well they are performing in school and as a marker of passage to the next level. But well-formulated and thoughtful feedback can accomplish this more effectively than a grade because this kind of feedback gives more specific information. And why not just use the different levels of education to measure progress? Either you demonstrate you’re ready for harder work, or you need to try again. Grades now seem redundant.

A deeper problem with grades, a more insidious one, is that they are based on biased standards of “good” and “bad” work. This is not just in language arts (my area). It’s true in math and other sciences too. Yes, there are right and wrong answers in math, but math teachers are also taking students on a journey, not just a destination. They too are dissecting ways at arriving to the answers, and ways to perform the journey as well as evaluating how quickly students should be taking the journey. Sadly, these biases can create more barriers for people often excluded from higher education: people of color, neurodiverse learners, and other communities that we could learn from if we gave them more room to show us their ways to learn. One of the things we’re learning as we make things more accessible is that these measures actually help everyone learn.

With the current emphasis on anti-racist work in our schools and lives, the conversation around the removal of grades is even more important.

Indeed, there are so many great conversations going on about this topic right now. Teachers are talking about ungrading, contract grading, and other strategies that remove grades or make assessment more collaborative. I am using labor-based grading contracts. These contracts are based on the fact that if you complete your school work, you are learning. I give completes or incompletes instead of letter grades, and students can negotiate revisions with me if they want to. I think this makes a lot of sense. Isn’t the purpose of homework to help students learn? If my homework isn’t accomplishing this, then I need to rethink what I’m assigning. Learning is not about “work” or “labor” though it is hard work and laborious at times. Learning should be more of a conversation, a belonging to a curious community. In other words: it should be fun!

While I do still have to give a grade at the end of the semester, and my contracts don’t completely remove anxiety, they have been largely beneficial with my community college-level English language learners. Using a grading contract has promoted the dialogue that is key to forming intrinsic motivation for learning. Because I don’t give grades, students pay more attention to my feedback on their work. They can’t look at a letter to tell them where they stand, so they need to dive into my comments and find the information they need to grow. They need to come talk to me if they want to fix their work or improve. Because there is actual dialogue, students have opportunities to advocate for what they need or what they are doing for certain pieces of work. This reduces the chances that my own biases and preferences will dominate their learning environment. I still love to learn, and making room for other voices and other intelligences is what makes teaching exciting to me. In turn, I model my learning skills for students, and they can learn from me how best to apply them to grow. I believe that modeling a life where learning thrives is the greatest value I offer I as a teacher.

Many other teachers who are using these types of collaborative assessment methods are reporting similar results. Google key words like “collaborative assessment” and “grading for equity” and see the conversations that are happening. They are striking and enlightening.

I’ll take a moment to mention what I am not saying in this piece. I am not advocating that we remove standards or real benchmarks from education. These are useful tools, but they should be revised consistently to reflect our own learning about quality education and what our students need on a regular basis. Good benchmarks motivate us all to measure our growth.

I’m also not saying that everyone should pass our classes just by doing the work. We all learn non-linearly and at different paces. We’ve known that for a while, and there can be room for failure. Indeed, there should be room for failure, but let’s always be looking for ways to increase the dialogue around arriving at the standards. Rubrics are good for consistency, but I think they work best when seasoned with real conversations.

I’d also like to note, I’m not advocating for the changing of the A-F grades to stars, storm clouds, or sparkly shit. That’s the same wolf in different clothing.

For teachers who have 100 students or more or are just feeling overwhelmed, I offer this encouragement: I don’t think you need to have a personal chat with each individual student about their journey. There are wonderful ways to use tech to make feedback more human while keeping it efficient and to create space for that dialogue when needed. My personal favorite is recorded comments. These are much faster to generate, and students can still hear the tone of my voice. I am all for being kind to ourselves as teachers.

What I hope to achieve in this piece is to contribute to the conversations that are currently taking place regarding taking grades out of school. These are not new conversations. It’s just that recent events, such as the pandemic (how to grade students fairly as we are all going through this tremendous crisis) and anti-racism movements, have refreshed them.

For people interested in the nuts and bolts of what removing grades looks like, below are some resources that helped me and inspired this piece:

“When Grading Less Is More” by Colleen Flaherty in Inside Higher Ed

UDL [Universal Design for Learning] At A glance by CAST

“Our Kids Are Not Broken” by Ron Berger in The Atlantic

And there are many others out there.

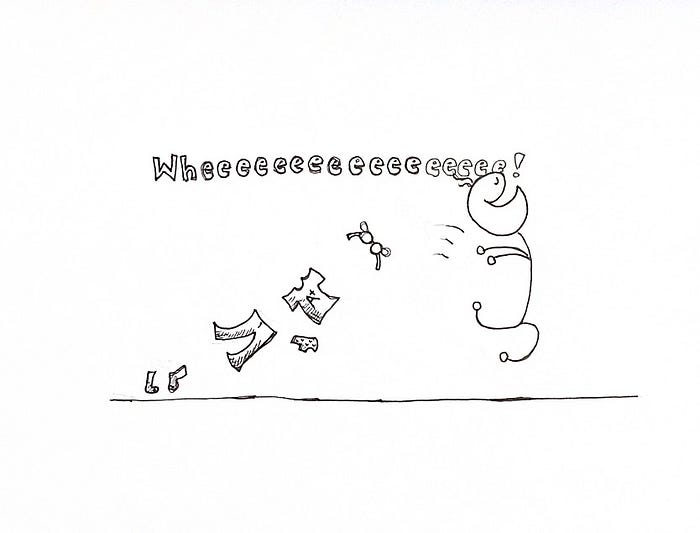

Not everyone can be homeschooled. I realize this is a pretty privileged experience, and I live in deep appreciation for how it has shaped my life. But what if school, and our larger educational institutions in general, could offer this experience to all? Of making learning a chance to give our curiosity full reign in a community of learners without the fear of getting marked down for going too far in our experiments or exploration of a topic that interests us that may be different from the course material? It’s never too late to enjoy the naked freedom of learning as play. I think it’s a pretty damned cool way to learn, and the human brain is amazing in that way: it will change and grow no matter what age we are. It will be some work in the beginning to change our grading format, but the pay off is worth it. Let’s go gradeless!